The Last Trip Home

The last time I made a record was in 1980, when they were still "records". Roseville Fair was self-financed/published (with Paul Mills as producer), so I was honored and delighted when Andy Cohen approached me to do this one. I've known Andy, like many of the songs here, since the 1970s, when I was still a college student and he was already an experienced traveling musician. It's astonishing when I look back now to realize what an amazing cohort of folk musicians we had in and around Ithaca, NY at that time, when English singers John Roberts and Tony Barrand and banjo virtuoso Howie Bursen were Cornell graduate students and Ken Perlman and I were undergraduates; and Ithaca was also home to string bands such as Country Cooking and Desperado, blues singer John Miller, and singer-songwriter Bill Steele. So many of us were inspired by the musicians who came to perform for the Cornell Folk Song Club and for Phil Shapiro's weekly Bound for Glory radio show on the student-owned and operated radio station, WVBR-FM. The show has been in reruns since the pandemic began, but I 'm sure it will be back. Its 40th birthday got a write-up in the New York Times.

All of my earliest connection with folk music traces back to Pete Seeger: my mother sometimes played his records of an evening, and my oldest sister, Lee Harter Kimmel, learned to play banjo when he visited her summer camp up along the Hudson River. She showed me some of the basics when I was about 13 or 14, around the time I began playing guitar seriously (I also had piano lessons starting at age five). That early contact might never have amounted to anything if I hadn't landed at Cornell in the early 1970s, where I was introduced first to the commercial folk scene, which was already waning, and then to the traditional folk scene. Phil Shapiro was almost the first person I met on arrival. He and Bill Steele (who himself was hugely influenced by Pete Seeger) did a lot to push me to learn banjo; Phil even lent me a banjo to learn on. I think it was attending a Mike Seeger concert that first led me to pick up autoharp, and the playing of Robin Morton of the Boys of the Lough and Alistair Anderson that led me to concertina. I experimented with many other instruments in those years; these are the ones that have stuck.

Between the Cornell Folk Song club's weekly concerts and Bound for Glory, I had two chances a week to hear and learn from established musicians with many different approaches. Among the first and biggest influences was Ed Trickett (1942-2022), whose taste in songs (and Drop D tuning!) was extraordinarily similar to my own and whose gentle, direct singing style was extraordinarily communicative. I also learned a lot from listening to Lou Killen (1934-2013), a master ballad singer who could make a more powerful impact singing unaccompanied than most singers can make backed by a full band and a troupe of dancing monkeys. Listening to Lou taught me to put the rhythms in the words of the song first, and keep the accompaniments subservient to them. If you're not going to communicate the words and sense of the song, why sing them? Two other major influences, both Scottish: Archie Fisher, who showed me the favorite British guitar tuning DADGAD and sang so many wonderful songs (and whose 1976 Folk Legacy record, "Man With a Rhyme" I played on) and Dick Gaughan, whose work translating Irish and Scottish fiddle tunes onto guitar suggested approaches for doing the same with banjo, and whose heavily ornamented singing style taught me that voice and accompaniment can usefully have contrasting rhythms.

Regarding this CD, I would particularly like to thank John Ive, who welcomed me into his home studio and worked tirelessly to produce the best possible sound. It would be wrong to underplay his skill and determination by calling it "magic", but that's what it seemed like.About the Songs

I was startled to realize that I've known and sung some of these songs for nearly 50 years without ever inquiring further into their origins than the person I heard them from. Links in the chain matter, and so I've done my best to provide more detail about them and their origins.

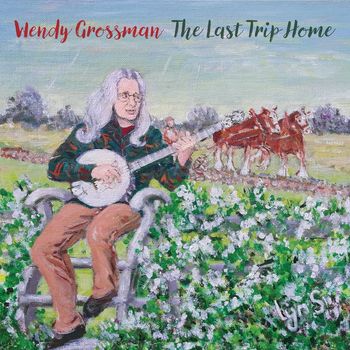

The Last Trip Home (Davy Steele) This ode to the Clydesdale horses that worked Scottish farms for generations was written by Davy Steele (1948-2001) during his time as lead vocalist and guitarist with the Battlefield Band. The song highlights the passing out of use of Clydesdale horses in agriculture between the 1930s and 1960s as they were progressively replaced by tractors, a story Steele is reported to have been told by a bandmate who'd heard it described by a caller to a radio show. Clydesdales have since made a comeback as carriage horses and are often seen in parades, processions, and the Household Cavalry. (More here and at Wikipedia).The song was suggested to me by the Scottish singer Hector Gilchrist (1940-2022), who thought banjo might go well with it. This turned out to be true - although I excuse my initial skepticism by noting that to make it true I had to abandon my usual frailing/clawhammer style and switch to finger picking. Played on banjo in open G, capo 2, and baritone guitar in Drop D (key of A) tuning.

This CD might not exist at all without Hector, whose broad knowledge of local studios led him to introduce me to John Ive and his studio. Sadly, Hector died unexpectedly while we were approaching the final stages of recording. This song is for him.

The Gold Ring (Traditional, arr. Wendy Grossman) Jigs on clawhammer banjo are one of my specialties (for more, try Howie Bursen, who taught me how to do it, or Ken Perlman, who I believe also learned from Howie.) The secret is getting comfortable with the rhythm and with hitting downwards twice in a row. This one I originally heard from the Boys of the Lough; it's on their Second Album. Banjo in open G. The Laird o' Drum (Child 236, Roud 247; traditional, arr. Wendy Grossman) I think this was the first real ballad I ever learned. It came from the singing of George and Vaughan Ward, who played it at a Cornell Folk Song Club concert around 1974; they learned it from the Scottish source singer Elizabeth Stewart (1939-2022), whose family were famed for their knowledge of balladry and folklore. The ballad is based on a true story: the laird in question, Alexander Irvine, the 11th Laird of Drum, was first married to the somewhat aloof and aristocratic Mary Gordon, and, after she died, chose for his second wife Margaret Couts, a 16-year-old shepherdess. That part is creepy by modern standards: he was 63 at the time. What I like about the ballad, though, is her father's insistence that she be treated as a wife and not a servant, and her own post-marital insistence, despite his family's snobbery (here represented by his brother John) that they were equal - the last verse, unusually, gives the woman the final word. In real life, the marriage lasted six years until he died in 1687, and produced four children. Guitar in drop D, capoed three. The Wife of Usher's Well (Child 79, Roud 196; traditional, arr. Wendy Grossman) I learned this song in the mid-1970s from Bill Destler. Bill gives its origin as Virginia singer Texas Gladden (1895-1966), who sings it unaccompanied under the title "The Three Babies" on her CD Texas Gladden: Ballad Legacy, which was recorded in 1941 by Alan Lomax and reissued by Rounder Records in 2001, The ballad has many versions in both the US and Britain; the story of the woman whose children have died away at (magic!) school and needs to make peace with their deaths is timeless. Like many ballads about grieving, the spirit of the dead can't rest until the living mourner lets go. Banjo in mountain modal. South Wind In this Irish song (as in the Scottish song "Norland Wind"), a homesick person discusses their longing for their former home with the passing wind. In this case, the person is living in Munster, and in the first and third verses pines for their home country of Mayo (while stipulating that life in Munster isn't at all bad); the south wind answers in the second verse to boast of its warming influence and promise to help. The tune was already well-known and widely played on its own when Archie Fisher showed up in the US circa 1976 with the words. On his Folk Legacy record, Man With a Rhyme, he gave the origins this way: "Composed by Donal O'Sullivan from the translation of the song by 'a native of Irrul, County Mayo, named Domhnall Meirgeach Mc Con Mara (Freckled Donal Macnamara)' and published in O'Sullivan's Songs of the Irish (Crown, New York, 1960)." Played on tenor-treble concertina in Bb. Mary Hamilton (Child 173; Roud 79; traditional, arr. Wendy Grossman) It is rare to hear a version of this classic ballad that *isn't* the one popularized by Joan Baez in 1960. I heard this one from Folk Legacy Records co-founder Caroline Paton (1922-2019), who learned it from the Texas singer and musicologist Hally Wood (1922-1989), and preferred it immediately, in part because the different tune leads you to hear the story afresh. The basic story is the same: a personal attendant to the queen becomes pregnant by the king, kills the resulting child, and is caught and hanged for it. Caroline sang it unaccompanied; this is the only song in this collection that I play in "standard" guitar tuning, expanded by the baritone guitar in drop A, capoed two, to add some bass notes of doom. Griselda's Waltz (Bill Steele) My old friend Bill Steele (1932-2018 and no relation to Davy Steele), best known as the writer of the environmental anthem "Garbage!", wrote this relatively late in his life. As he told the story, he was driving down the road in his van when the tune came to him, and he thought it was the best tune he'd ever written. I put it on the autoharp (because autoharps love waltzes!) and added the key change. Starts in Bb, ends in C.The story is, of course, a fractured version of "Cinderella", in which one of the stepsisters (the Griselda of the title) colludes with Cinderella to captivate her prince in hopes of rewards later. Bill did a lot of research to decide on the details in this version. Many older versions have Cinderella's slipper made of fur, as it is here (although New Jersey singer Mike Agranoff insists that "glazier" scans just as well as "furrier"). You may wonder what happened to the other sister. Bill couldn't figure out how to include her in the story, so rather glossed over her. He observed later that Gregory Maguire, whose 1999 novel Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister also retells the Cinderella story, had the same problem. Someone needs to write a song about this neglected woman!

In reviewing this, St Paul folklorist Robert Waltz suggests that "Griselda" may be a mishearing of Disney's name for one of the sisters, Drizella. The Perrault version of the tale, which appears to be Bill's main source and which Andrew Lang used as the main source for his Blue Fairy Book, doesn't name the sisters, but gives them distinct personalities, in which one was at least somewhat kind to her abused stepsister.

(If this were an LP with A and B sides, the break would be here.

Mominette (Maxou Heintzen) The 2022 San Francisco Spring Harmony virtual camp featured a session in which a large group called Fete Musette hung out in a breakout room playing French country dance tunes at a slow pace so anyone could learn the tune and join in. This schottische was the standout among them. Written in 1981 by the French musician Maxou Heintzen, it has since been shuffled around, adapted, renamed multiple times, and even refashioned as a jig. I managed to find its original name by typing in the first few notes to the invaluable FolkTuneFinder.com site, which knew it at once. Played and overdubbed on the tenor-treble concertina in D minor. One, I Love (Jean Ritchie) The great Kentucky singer Jean Ritchie (1922-1915) explained the genesis of this song in a 2001 posting on Mudcat.org, the invaluable site for folk song lyrics and discussion. She heard a song fragment - the first verse - while listening to group practicing banjo (all male, because playing banjo was not ladylike), and slowed it down, added her own tune, and wrote more verses, borrowing some lines and images from other songs. I know roughly when I learned this - around 1981-1982 - but not how. I *think* it was from one of her recordings. Guitar is in open g minor, capoed two, and (fingerpicked) banjo in open g minor, also capoed two. Queen Amang the Heather (Traditional, arr. Wendy Grossman) This song comes from the Scottish traditional singer Belle Stewart (1906-1997). I first heard it from several of the Scottish singers whose music arrived in the US in the 1970s - Archie Fisher, Dick Gaughan, and others, usually either with guitar or unaccompanied. As in "The Laird o' Drum", a rich guy goes out in the countryside and immediately proposes marriage to a pretty teenaged girl keeping sheep, who initially refuses him because of the vast class differences. In both, they end up (presumably) happily coupled. I like to think the age gap is a lot less here than in "The Laird o' Drum"!There is no real excuse for playing it on the banjo except that the sparseness of the banjo and of Scottish music seem to go well together, and in my opinion there really ought to be a Scottish mountain banjo tradition. The banjo is tuned in mountain modal.

The Jeannie C (Stan Rogers) The Canadian songwriter Stan Rogers (1949-1983) wrote dozens of wonderful songs in his all-too-short life. Some of the best, like this one, were those in which he illuminates the lives of Canadian working people. I believe it's a sign of a great songwriter that the inner logic of the words makes them easy to learn; this one about a fisherman's grief at a catastrophic accident that costs him the boat that has been his partner throughout his working life practically sings itself. Guitar in open C, plus a drizzling of concertina. The Surveillance Waltz (Wendy Grossman) For the 2005 Computers, Freedom, and Privacy conference, the organizer of the Big Brother awards, given to the worst privacy violators of the day, thought it would be fun if I sang Bill Steele's song "The Walls Have Ears", a remarkably prescient imagining of something more like our time than 1974, when the Watergate discovery that Nixon's conversations had all been recorded inspired him to write it. Because the tune doesn't have much variation, I began noodling on the only instrument I had with me, the autoharp, to find something I could play between verses to liven it up a little. Instead, I got this four-part waltz in A minor. My Sweet Wyoming Home (Bill Staines) I first met Bill Staines (1947-2021) in 1973, when we hired him to do a concert for the Cornell Folk Song Club straight off his demo tape. This was before folksingers had media packs and sent photographs, and when we went to make the poster we had no idea what he looked like. But we knew he played guitar, so our resident poster-maker, John Bric, made a poster with a silhouette of a man sitting on a stool playing guitar. How could we go wrong? As the world and all now knows, Bill was left-handed and played the guitar upside down and backwards. Bill traveled more than three million miles around the US singing the hundreds of songs he wrote, likely the all-time record for miles driven by a folksinger. "I have the log books," he said back around the time he hit two million miles.I know this wasn't the first song I ever learned of Bill's - that was "Sweet Winds Blowing" - but I think it was the second, as it was on his first album, issued in 1975. ("Roseville Fair", which I recorded in 1980, was later; I was in the audience at I think its first performance, at the Fool Killer in Kansas City, Missouri in 1977 or so and started singing it immediately, and Bill didn't record it until 1979). Other people tell me they remember me singing it since the mid-1970s. I haven't spent much time in Wyoming as a matter of fact, but on my most recent drive across, in 2015, I was reminded what a really beautiful state it is. Lead guitar is in open G, capoed two, and the baritone guitar is in what would be drop D if it were a normal guitar, which makes it drop A.

A note about tunings

One of the first things every banjo player learns is that different keys require different tunings. If you're a guitar player as well, transferring tunings between the two is very easy because the top four strings are close enough so that many of the chords are the same. Here are the ones I've used on this CD. Notes are from bass to treble.

Guitar:- Drop D ("My Sweet Wyoming Home", "The Laird o' Drum"): D A D G B E

- Open G ("My Sweet Wyoming Home", lead guitar): D G D G B D

- Open C ("The Jeannie C"): C G C G C E

- Open g minor ("One, I Love"): D G D G Bb D.

- Drop A* ("My Sweet Wyoming Home", "Mary Hamilton", "The Last Trip Home"): A E A D F# C#

- *exactly the same as Drop D on a standard guitar

- Mountain modal, or G modal ("Queen Amang the Heather", "The Wife of Usher's Well")

- Open G ("The Gold Ring", "The Last Trip Home"): g D G B D

- Open g minor ("One, I Love")

About the instruments:

Autoharp: This autoharp was made by Greg Schreiber (www.schreiberautoharps.com); it has 37 strings, fine tuners, and 21 quick-change chord bars - basically, it's a luxury autoharp. We have Bryan Bowers to thank for the idea of reorganizing the chord bars to make it easier and more ergonomic to play tunes on the autoharp; the downside is that many autoharp players have their own ideas about the optimal layout (with the unfortunate result that a lot of autoharp players can't play anyone else's harp). Most layouts are largely based on Bowers' order, because one great benefit of his rearrangement is that the most-used chords remain in the same relative positions in every key. In other words, a key shift like the one in "Griselda's Waltz" may sound impressive but is actually incredibly easy to do as long as the first button you hit is the right one. My personal layout is documented on my website at https://www.pelicancrossing.net/autoharp.htm, though with one exception: most of the time, I have a C suspended 4 chord in the top left position where the very weak Ab chord is indicated. Banjo This banjo was originally an Orpheum Number 2 tenor banjo. John Ellis, then-owner of the Guitar Workshop in Ithaca, NY (the precursor of today's Guitar Workshop), sold it to me in 1975 and arranged for it to be converted to a five-string by Al Worthen, of Old Forge, NY. I doubt I could play the way I play on anything else - the slim neck and the excellent action make it easy (at one time, Howie Bursen and Bill Destler had near-identical banjos to this one). I use medium-gauge strings. Guitars: My main guitar is a 1984 Taylor jumbo I bought used from the Ithaca Guitar Works in 1985 when I went there looking for "something like a really good Guild jumbo like the one Ed Trickett has". I string it with medium gauge strings except for the bottom E string, which is extra-heavy (.059) so I can tune it down to C without buzzing. The baritone guitar is a 2010 Taylor I found on eBay and is strung with a standard set of medium-gauge baritone strings. Concertina: My concertina is a 56-key Wheatstone tenor-treble that at some point was altered to place a low Bb stashed away on the lower left. The serial number dates its manufacture to September, 9, 1912; I got it from Chris Algar at Barleycorn concertinas in 2008, many years after the concertina that appeared on Roseville Fair was stolen. He says that the presence of that low Bb was usually done to suit the requirements of the Salvation Army, and also that this particularly concertina was, for a while, owned by Charles Bramwell Richardson, a well-known music hall performer from (if I remember correctly) Birmingham.Personnel

- Wendy Grossman: vocals, guitar, baritone guitar, banjo, concertina, autoharp

- John Ive: recording engineer

- Recorded at IveTechMedia Studios

- Cover art by Lyn Stocks

- Patron saint: Hector Gilchrist

I used to be a *full-time* folksinger...

Back to front

Back to folk

On to email