The need to know

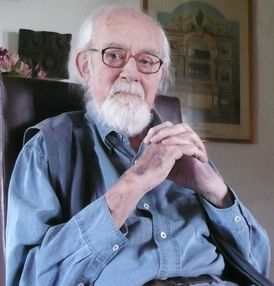

"How wonderful," Antony Jay said in 1994, according to William Heath (R), when he was shown the internet for the first time. "I wonder what the government will do to ruin it." Arguably, we're finding out.

Jay is one of the two people net.wars quotes most often, the other being his collaborator, Jonathan Lynn. Together, they wrote Yes, Minister, the classic 1980-1988 BBC sitcom that taught the UK how its government really worked. Margaret Thatcher, whom Jay admired, loved the show so much she tried writing a scene for it, and many other politicians have called it simply "a documentary".

"Most comedy writers come from a different world," Jay says by way of explaining its success. "They don't really know much about politics." Jay, however, was the early 1960s editor of the BBC current affairs program Tonight. "I'd had a long career in the political world. I knew what went on a bit - I knew a lot of politicians, so we wrote from knowing something about the world, rather than just writing about an idea of things."

In addition, "I'd had quite a lot to do with civil servants in various things I'd done with politics." The difficulty was their endemic discretion. "They wouldn't tell you anything they didn't think you knew anyway. But if you made a good guess they would then unveil things." By contrast, "Politicians told you the lot, so we got a lot from them and because what we got from them was helpful we could then sort of use that with civil servants to get them to tell us." . Then as now, buying lunch and laying on good booze was helpful in encouraging disclosures. "The more they drank, the more they told you."

Jay got the idea in 1977, but it took until 1979 for Lynn to find the time to begin writing. "I'd written a lot of comedy," Jay says, "but training films for business." The reference is to Video Arts, the company he founded in 1972 for which he wrote scripts that used humor to teach subjects such as how to run meetings. Many of these were performed by John Cleese and are fun to watch even if you don't want to run a company. Cleese, whose own Fawlty Towers was broadcast in 1975 and 1979, was, it transpires, the other person Jay asked to be his co-writer. Cleese was too busy.

"It just happened that [the idea for the show] was completely new," he says. "Politicians had been fairly common, but civil servants - not just pouring out the tea but running the country - were not." The show's audience wasn't huge, but, "The people who did like it, *really* liked it."

As topical as Yes, Minister seems - episodes like "Big Brother" or "The Death List" episodes are as freshly relevant now as in the early 1980s - it's actually based on timeless themes that don't date. Similarly, Jay's books, such as 1996's Management and Machiavelli, use historical analogues to explain business power structures, whose rules are as old as humanity.

In some ways Jay found writing television comedy simpler than writing business scripts. "Business programs always show the right way to do it as well as the wrong way. On television, you don't have to do that. You just show the wrong way, and everybody laughs."

In some ways Jay found writing television comedy simpler than writing business scripts. "Business programs always show the right way to do it as well as the wrong way. On television, you don't have to do that. You just show the wrong way, and everybody laughs."

That's the other reason Yes, Minister has dated so little: the main situation hasn't changed much. Many people claim that both politicians and civil servants have wised up and adapted their tactics after imbibing the show's lessons. Yet a personal straw poll of a few civil servants indicates that they still see getting things past the minister without their noticing as a usefully efficient strategy. The show seems clearly still relevant, even to those inside government today. Making something of that significance - "That was the fun."

It's usually pointless to ask a fiction writer how to fix something in the real world. Jay's background makes him the exception, so we had to ask: is there any way to change the push for surveillance. Sir Humphrey says (Yes, Prime Minister, Season 2, episode 1, "Man Overboard) "I need to know *everything*. How else can I judge whether or not I need to know it?" Is that it?

"If you get into a bureaucracy," Jay says, "control becomes a very important thing. They don't think of it like that, they just think of doing it right. But actually what they're doing is keeping out the things they don't want and pushing the things that they do." He is unsurprised at the suggestion that recent legislative moves have sought to legalize things that Edward Snowden's revelations showed were already happening.

"Control is the great thing for government - they want to control what happens, control what information gets out, and they're powerful and they have money, and the rest of us are not organized and so the government kind of does it." From their point of view, he says, "They don't see it as anything other than good government, but actually it's control government, which is what they want."

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.We apologize for having to turn off comments on this blog, which was getting hammered by spambots.