Have robot, will legislate

The mainstream theme about robots for the last year or so has been the loss of human jobs. In 2013, Oxford Martin professors Carl Bendikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimated that automation would eliminate 47% of US jobs in the next 20 years. This year, McKinsey estimated 49% of work time could be automated - but slower. In 2016, the OECD thought only 9% of jobs were at risk in its 21 member countries. These studies' primary result has been thousands of scary words: the five jobs that will go first (which concludes no job is safe). Eventually, Bill Gates' suggested robots should pay taxes if they've taken over human jobs.

The mainstream theme about robots for the last year or so has been the loss of human jobs. In 2013, Oxford Martin professors Carl Bendikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimated that automation would eliminate 47% of US jobs in the next 20 years. This year, McKinsey estimated 49% of work time could be automated - but slower. In 2016, the OECD thought only 9% of jobs were at risk in its 21 member countries. These studies' primary result has been thousands of scary words: the five jobs that will go first (which concludes no job is safe). Eventually, Bill Gates' suggested robots should pay taxes if they've taken over human jobs.

The jobs issue has been percolating since 2007, and it and other social issues have recently spurred a series of proposals for regulating robots and AI. The group of scientists who assembled last month at Asilomar released a list of 23 principles for governing robots. In January, a group at London's Alan Turing Institute and the University of Oxford called for an AI regulator to ensure algorithmic fairness. The European Commission has thought about legal status. Finally, the new research group AI Now has released a report (PDF) with recommendations aimed at increasing fairness and diversity.

More than in past years (2016's side event and main event, 2015, 2013, and 2012), the discussions at this year's We Robot legal workshop reflected this wider social anxiety rather than create their own.

More than in past years (2016's side event and main event, 2015, 2013, and 2012), the discussions at this year's We Robot legal workshop reflected this wider social anxiety rather than create their own.

For me, three themes emerged. First, that the fully automated intermediate systems of the future will be less dangerous than the intermediate systems that are already beginning to arrive. Second, that changing the lens through which we look at these things is valuable even if we dislike or disagree with the altered lens that's chosen. Finally, efforts to regulate AI may be helpful, but implemented in entirely wrong-headed ways. This is the threat We Robot was founded to avoid.

At the pre-We Robot event on the social implications of robotics at Brown University. Here, Gary Marcus argued that we will eventually have to build systems that learn ethics, though it's not clear how we can. With this in mind, he said, "The greatest threat may be immature pre-superintelligence systems that can do lots of perception, optimization, and control, but very little abstract reasoning." In columns such as this one from The New Yorker, Marcus has argued that the progress made so far is too limited for such applications; a claim with which a recent blog posting by data scientist Sarah R. Constantin concurs.

At We Robot itself, the paper by Marc C. Canellas et al examined how to frame regulation of hybrid human-automation systems. This is of particular relevance to"self-driving" cars (autocars!), where partially automated systems date to the 1970s introduction of cruise control. Last year, Dexter Palmer's fascinating novel Version Control explored a liability regime that, like last year's paper on "moral crumple zones" by Madeleine Elish, ultimately punished the human partner. As Canellas explained, most US states assign liability to the driver. Autocars present variable scenarios: drivers have no way to test for software defects, but may still deserve blame for ordering the car to drive through a blizzard.

The extent to which cars should be fully automated is a subject for debate already. There is some logic to saying that fully automated cars should be safer than partially automated ones: humans are notoriously bad at staying attentive when asked to monitor systems that leave them nothing to do for long stretches of time. Asking us to do that sort of monitoring is the wrong way round, since that's what computers, infinitely patient, are actually good at. In addition, today's drivers have thousands of hours of driving experience to deploy when they do take over. This won't be true 15 years from now with a generation of younger drivers raised on a steady diet of "let me park that for you". The combination of better cars but worse humans may be far more dangerous.

Changing the lens was the subject of Kristen Thomasen's paper, Feminist Perspectives on Drone Regulation (PDF). Thomasen says she was inspired by a Slate article by Margot Kaminsky that called out the rash of sunbathing teenager stories that are being used to call for privacy regulation. Thomasen's point was that the sunbathing narrative imposes a limited and paternalistic definition of privacy as physical safety and ignores issues like information imbalance. Diversity among designers is essential: even the simple Roomba can cause damage when designers fail to imagine people sleeping on the floor.

Both these issues inform the third: how to regulate AI. The main conclusion: many different approaches will be needed. Many questions arise: how much and what do we delegate to private actors? (See also fake news, trolling, copyright infringement, and the web.) Whose ethics do we embed? How do governments regulate companies whose scale - "Google scale", "Facebook scale", not "UK scale" - is larger than their own? And my own question: how do you embed ethics when the threat is the maker, not the machine, as will be the case for the foreseeable future?

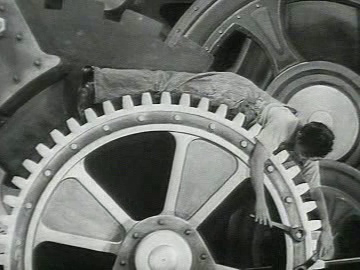

Illustrations: Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1036); Pepper, at We Robot 2016.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.