Who needs the internet?

In August 1999, I was commissioned by the then-new magazine ComputerActive to write a piece on "technostress" - how people handle information overload. It turned out that everyone I knew had a strategy, which usually involved being a refusenik to some particular thing. A science fiction writer friend, for example, explained that he never made phone calls. If someone wanted to talk to him enough, they'd call him. His sister had no answering machine so she wouldn't ever have to call anyone back. Someone else had an email address but never disclosed it to anyone because "some people spend two hours every morning just doing their email!"

In August 1999, I was commissioned by the then-new magazine ComputerActive to write a piece on "technostress" - how people handle information overload. It turned out that everyone I knew had a strategy, which usually involved being a refusenik to some particular thing. A science fiction writer friend, for example, explained that he never made phone calls. If someone wanted to talk to him enough, they'd call him. His sister had no answering machine so she wouldn't ever have to call anyone back. Someone else had an email address but never disclosed it to anyone because "some people spend two hours every morning just doing their email!"

An investment bank researcher went to bed at 9pm every night to escape the constant stream of information - and the after-effects of a long day spent in an over-airconditioned office under too-bright fluorescent lighting surrounded by the cacophony of the trading floor. One academic during a particularly stressful time kept his home undisturbed by having no phone there. And so on. Around then, I remember asking a Labour MP who was opining at length about What Needed to Be Done about the internet, "Do you answer your own email?" He looked at me as if I'd asked him if he did his own grocery shopping. "My secretary does it." Right. But he's the one making policy about it.

Since then, the influx of information has increased, but we're more used to it. Even so: there are still hold-outs. A new acquaintance (late 60s, I guess) refuses to have either a mobile phone or use the internet. "People can phone me," she said, which sounds reasonable until you talk to someone who needs to communicate with her regularly: "It drives me crazy."

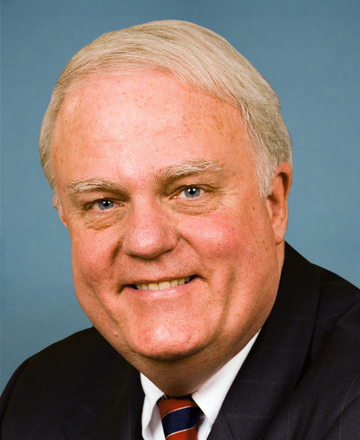

This week, Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI) justified voting to overturn the FCC's privacy rules and allow ISPs to exploit their subscribers' browsing histories by saying, "Nobody has to use the internet". As "Ccumming" commented at Ars Technica observed, "To prove his point he should not use the internet for his re-election campaign and see how it goes."

Sensenbrenner is 73, which means that the internet has only been available to him for two-thirds of his life and it's unclear if he's ever used it himself. I'm ten years younger, and the internet-less proportion of my own life is 58%, and shrinking steadily. When you can remember living a rich, full life without the internet, it surely seems more luxury than necessity. However, the switch from "who would want that?" to "who really needs that?" to "what do we do about the people who don't have it?" was amazingly short - people watching the upward takeup trajectory began fretting about the digital divide in the 1990s. Lastminute.com founder Martha Lane Fox has been campaigning for years to get that last recalcitrant percentage online.

In September 2016, Pew Research reported that 13% of American adults don't use the internet, a number that hasn't budged in three years. Who are they? Pew asked. They are: 41% of over-65s; a third of adults who didn't finish high school; and disproportionate numbers of both rural residents and people in households with annual incomes of less than $30,000. So: older people, less-educated people, poorer people, and rural people. It's easy to surmise the latter two groups may lack affordable access. For comparison, in the UK, Ofcom finds that 86% of adults have the internet at home, and spend an average of 25 hours a week using it. So: 14% don't have it, about half of whom don't intend to get it. Most of these (83%) are older people. Half don't think they need it; a quarter (mostly over 65) think they're "too old"; another quarter don't want to "own a computer". A declining number (15%) think it's too expensive.

In September 2016, Pew Research reported that 13% of American adults don't use the internet, a number that hasn't budged in three years. Who are they? Pew asked. They are: 41% of over-65s; a third of adults who didn't finish high school; and disproportionate numbers of both rural residents and people in households with annual incomes of less than $30,000. So: older people, less-educated people, poorer people, and rural people. It's easy to surmise the latter two groups may lack affordable access. For comparison, in the UK, Ofcom finds that 86% of adults have the internet at home, and spend an average of 25 hours a week using it. So: 14% don't have it, about half of whom don't intend to get it. Most of these (83%) are older people. Half don't think they need it; a quarter (mostly over 65) think they're "too old"; another quarter don't want to "own a computer". A declining number (15%) think it's too expensive.

Sensenbrenner was answering a constituent, who was trying to differentiate between content companies like Google, for which there are alternatives (try DuckDuckGo), and ISPs, which in many parts of the US are effective monopolies. By contrast, in the UK, where regulation has forced BT to open access to its infrastructure to competitors, in many locations there are five or six consumer ISPs to choose among, and many more business ISPs. Even so, in 2014 when Cybersalon collected frustrations at the Web We Want festival, inadequate access came top of the list.

So: who doesn't need the internet? In the early 1990s, the snide response would have been, "People with friends." Now, the profile of the person who can live without it looks something like this: has no schoolchildren (because homework is increasingly assigned, completed, and turned in online); has no need to apply for jobs (because job applications...ditto); is their own boss; either has no interest in news or still has a local newspaper and/or TV station; still has a nearby bank, book store, movie theater, grocery store, and whatever else they require to live their idea of a civilized life; has access to traditional media to publish and distribute whatever they want; and is either in no demand at all and doesn't care, or in so much demand that they can set the terms of engagement, like my friend who doesn't make phone calls.

So what Sensenbrenner means is that *he* doesn't need the internet. He is in a small and shrinking class. If he used the internet, he would know this.

Illustrations:: Jim Sensenbrenner; Martha Lane Fox.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.