Send lawyers, guns, and money

There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones, people around Las Vegas disagree with President Donald Trump's claim that now is not the time to talk about gun control. The National Rifle Association probably agrees; in the past, it's been criticized for saving its public statements for proposed legislation and staying out of the post-shooting - you should excuse the expression - crossfire.

There are many reasons why, Bryan Schatz finds at Mother Jones, people around Las Vegas disagree with President Donald Trump's claim that now is not the time to talk about gun control. The National Rifle Association probably agrees; in the past, it's been criticized for saving its public statements for proposed legislation and staying out of the post-shooting - you should excuse the expression - crossfire.

Gun control doesn't usually fit into net.wars' run of computers, freedom, and privacy subjects. There are two reasons for making an exception now. First, the discovery of the Firearm Owners Protection Act, which prohibits the creation of *any* searchable registry of firearms in the US. Second, the rhetoric surrounding gun control debates.

To take the second first, in a civil conversation on the subject, it was striking that the arguments we typically use to protest knee-jerk demands for ramped-up surveillance legislation to atrocious incidents are the same ones used to oppose gun control legislation. Namely: don't pass bad laws out of fear that do not make us safer; tackle underlying causes such as mental illness and inequality; put more resources into law enforcement/intelligence. In the 1990s crypto wars, John Perry Barlow deliberately and consciously adapted the NRA' slogan to create "You can have my encryption algorithm...when you pry it from my cold, dead fingers from my private key".

Using the same rhetoric doesn't mean both are right or both are wrong: we must decide on evidence. Public debates over surveillance do typically feature evidence about the mathematical underpinnings of how encryption works, day-to-day realities of intelligence work, and so on. The problem with gun control debates in the US is that evidence from other countries is automatically written off as irrelevant, and, more like the subject of copyright reform, lobbying money hugely distorts the debate.

The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article Inside the Federal Bureau of Way Too Many Guns. In it, writer and author Jeanne Marie Laskas pays a comprehensive visit to Martinsburg, West Virginia, where she finds a "low, flat, boring building" with a load of shipping containers kept out in the parking lot so the building's floors don't collapse under the weight of the millions of gun license records they contain. These are copies of federal form 4473, which is filled out at the time of gun purchases and retained by the retailer. If a retailer goes out of business, the forms it holds are shipped to the tracing center. When a law enforcement officer anywhere in the US finds a gun at a crime scene, this is where they call to trace it. The kicker: all those records are eventually photographed and stored on microfilm. Miles and miles of microfilm. Charlie Houser, the tracing center's head, has put enormous effort into making his human-paper-microfilm system as effective and efficient as possible; it's an amazing story of what humans can do.

The second issue touches directly on privacy. Soon after the news of the Las Vegas shooting broke, a friend posted a link to the 2016 GQ article Inside the Federal Bureau of Way Too Many Guns. In it, writer and author Jeanne Marie Laskas pays a comprehensive visit to Martinsburg, West Virginia, where she finds a "low, flat, boring building" with a load of shipping containers kept out in the parking lot so the building's floors don't collapse under the weight of the millions of gun license records they contain. These are copies of federal form 4473, which is filled out at the time of gun purchases and retained by the retailer. If a retailer goes out of business, the forms it holds are shipped to the tracing center. When a law enforcement officer anywhere in the US finds a gun at a crime scene, this is where they call to trace it. The kicker: all those records are eventually photographed and stored on microfilm. Miles and miles of microfilm. Charlie Houser, the tracing center's head, has put enormous effort into making his human-paper-microfilm system as effective and efficient as possible; it's an amazing story of what humans can do.

Why microfilm? Gun control began in 1968, five years after the shooting of President John F. Kennedy. Even at that moment of national grief and outrage, the only way President Lyndon B. Johnson could get the Gun Control Act passed was to agree not to include a clause he wanted that would have set up a national gun registry to enable speedy tracing. In 1986, the NRA successfully lobbied for the Firearm Owners Protection Act, which prohibits the creation of *any* registry of firearms. What you register can be found and confiscated, the reasoning apparently goes. So, while all the rest of us engaged in every other activity - getting health care, buying homes, opening bank accounts, seeking employment - were being captured, collected, profiled, and targeted, the one group whose activities are made as difficult to trace as possible is...gun owners?

It is to boggle.

That said, the reasons why the American gun problem will likely never be solved include the already noted effect of lobbying money and, as E.J. Dionne Jr., Norman J. Ornstein and Thomas E. Mann discuss in the Washington Post, the non-majoritarian democracy the US has become. Even though majorities in both major parties favor universal background checks and most Americans want greater gun control, Congress "vastly overrepresents the interests of rural areas and small states". In the Senate that's by design to ensure nationwide balance: the smallest and most thinly populated states have the same number of senators - two - as the biggest, most populous states. In Congress, the story is more about gerrymandering and redistricting. Our institutions, they conclude, are not adapting to rising urbanization: 63% in 1960, 84% in 2010.

Besides those reasons, the identification of guns and personal safety endures, chiefly in states where at one time it was true.

A month and a half ago, one of my many conversations around Nashville went like this, after an opening exchange of mundane pleasantries:

"I live in London."

"Oh, I wouldn't want to live there."

"Why?"

"Too much terrorism." (When you recount this in London, people laugh.)

"If you live there, it actually feels like a very safe city." Then, deliberately provocative, "For one thing, there are practically no guns."

"Oh, that would make me feel *un"safe."

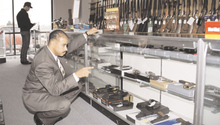

Illustrations: Las Vegas strip, featuring the Mandelay Bay; an ATF inspector checks up on a gun retailer.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.