Pay pal

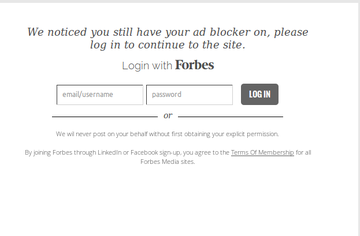

Is this the end of free, as Andrew Brown suggested? Forbes won't even show its front page to ad-blocked browsers. Wired owner Conde Nast posts giant screens dissing ad blockers. The Washington Post and the New York Times give you a countdown of the number of free articles you have left for the month and then demand you subscribe. Everyone, in short, wants to get paid, preferably before letting you read anything. The Guardian, with its polite little bottom banner suggesting you become a member, must be picking up a lot of (deadbeat) readers.

As I've noted before I do sympathize, just not enough to drop the ad-blockers that simultaneously shield against malware and the impossibility of reading past active animations.Mobile without ad-blockers is worse. Plus we've learned from years of internet use that there is always an alternative. The article on Russian state-run doping in athletics that the New York Times won't show me will be widely copied, summarized, expanded, and commented upon in the next few hours.

One problem is that we - or at least, I - don't read online the same way we do offline. With a print publication, I begin at the front cover and read straight through to the back cover, at least glancing at everything. Online reading is a butterfly experience. The separate click-and-wait for each article means you don't "read the paper". Natively, the web unbundles publications the way MP3s did albums. Every article is its own little island of "content" with its own little profit-and-loss calculation. Attempts to subvert this, such as full-publication Flash animations feel fake as well as frustrating.

That might not matter if current payment mechanisms weren't the journalism equivalent of cock-blocking. You want to read an article. Paying for it means loading another page, creating an account, filling out a form, paying - and then you're slopped back to the front page to log in and *then* search for the - what was it again? - article that piqued your interest. Sometimes, your only option is a permanent-until-you-cancel subscription to the whole paper, which requires thought and decision-making utterly disproportionate to your idle curiosity about what Jon Stewart said to Hillary Clinton. This is why Google is winning (for now).

Twenty-odd years ago, the solution was imminent: micropayments! Cryptographic precursors to bitcoin were going to enable tiny fees - a cent, a nickel - for reading articles. The technology was never simple enough for mainstream use - and still isn't. Donation experiments like tip jars using Paypal or Amazon and Flattr won't work for commercial publishers.

-thumb-240x343-272.jpg) A few weeks ago, the Meetup group Hacks/Hackers (half journalists, half techies) featured Dutch former journalist Alexander Klöpping explaining his effort to move things along in a more positive direction: the two-year-old, Blendle, which aims to pay publishers while giving readers a better experience.

A few weeks ago, the Meetup group Hacks/Hackers (half journalists, half techies) featured Dutch former journalist Alexander Klöpping explaining his effort to move things along in a more positive direction: the two-year-old, Blendle, which aims to pay publishers while giving readers a better experience.

Klöpping began with the desire to prove wrong the received belief that, "People won't pay for news" and a question: why was there nothing for journalism comparable to Netflix for movies or Spotify for music? What if there were? It took him a year to get all the Dutch publishers to sign up for his nascent platform. Blendle is now selling millions of articles every month to its 500,000 Dutch and German users and, with backing from the New York Times, launched in April in the US.

The scheme works like this. You have some money in an account that you top up periodically (say, $10 a time), and the service gives you a trial $2.50. You select from a display of article summaries, each of which has a modest price: 59 cents for Fear trumps hope, from the Economist, 29 cents for Going Dark, from the New York Review of Books. If the article disappoints, you request a refund. Klöpping is finding that people will pay for exclusive stories, quality journalism, analysis, deep background pieces, big interviews, and long-form stories - the things, in fact, traditionally give publications money and prestige.

Blendle is unquestionably designed with mobile phones and tablets in mind. On a desktop monitor, stories parade in a horizontal line, you scroll sideways to move from screenful to screenful of article text - not what we're used to, but workable. When you join - which has a 67,000-odd backlog, although freelances get favored treatment - the publications of interest you select determine the articles the system offers. The system's daily email suggesting articles is clunkier for me because I'm so habituated to clicking on an emailed link and reading the story a few seconds later. If your system is not logged in, clicking on a link brings up a screen that offers to email a temporary link that bypasses login. It's clever, but by the time I've fetched the email and loaded the article I could have found it on the publication's own website.

Still, Blendle seems a highly positive development. It offers publishers money they wouldn't get otherwise. It allows users to pay proportionately for what you want to read and seems to have no plans to mine your data. Those who pay - which Klöpping says is about 20% of signups - can bask in the golden glow of doing your bit to sustain quality jourrnalism. Which matters, because otherwise it will be Facebook Turks all the way down.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.