JAQing off

Years ago, when I used to be called in to do various types of discussion TV and radio programs as the token skeptic, a friend said I should turn these invitations down. He had done so himself, on the basis that absent specialists to provide "the other side" of the debate, the programs would drop the item.

Years ago, when I used to be called in to do various types of discussion TV and radio programs as the token skeptic, a friend said I should turn these invitations down. He had done so himself, on the basis that absent specialists to provide "the other side" of the debate, the programs would drop the item.

I was less sure, because before The Skeptic was founded, those programs did still run - with the opposition provided by a different type of anti-science. Programs featuring mediums and ghost-seers would debate religious representatives who saw these activities and apparitions as evil, but didn't doubt their existence or discuss the psychology of belief. So I thought the more likely outcome was that the programs would run anyway, but be more damaging to the public perception of science.

I did, however, argue (I think in a piece for New Scientist that matters of fact should not be fodder for "debate" on TV. "Balance" was much-misused even in the early 1990s, and I felt that if you defined it as "presenting two opposing points of view" then every space science story would require a quote from the Flat Earth Society. Fortunately, no one has gone that far in demanding "balance". Yet.

Deborah Lipstadt, opened her book Denying the Holocaust with an argument like my friend's. She refuses to grant Holocaust deniers the apparent legitimacy of a platform. This is ultimately an economic question: if the producers want spectacular mysteries, then the skeptic is there partly as a decorative element and partly to absolve the producers of the accusation that they're promoting nonsense. The program runs if you decline. If they want Deborah Lipstadt as their centerpiece, then she is in a position to demand that her fact-based work not be undermined by some jackass presenting "an alternative view".

Maybe that should be JAQass. A couple of weeks ago, Slate ran a piece by AskHistorians subreddit volunteer moderator Johannes Breit. He and his fellow moderators, who sound like they come from the Television without Pity school of moderation, keep AskHistorians high-signal, low-noise by ruthlessly stamping on speculation, abuse, and anything that smacks of denial of established fact. The Holocaust and Nazi Germany are popular topics, so Holocaust denial is a particular target of their efforts.

"Conversation is impossible if one side refuses to acknowledge the basic premise that facts are facts," he writes. And then: "Holocaust denial is a form of political agitation in the service of bigotry, racism, and anti-Semitism." For these reasons, he argues that Mark Zuckerberg's announced plan to control anti-Semitic hate speech on Facebook is to remove only postings that advocate violence will not work: In Breit's view, "Any attempt to make Nazism palatable again is a call for violence." Accordingly, the AskHistorians moderators have a zero-tolerance policy even for "just asking questions" - or JAQing, a term I hadn't noticed before - which in their experience is not innocent questioning at all, but deliberate efforts to sow doubt in the audiences' minds.

"Just asking questions" was apparently also Gwyneth Paltrow's excuse for not wanting to comply with Conde Nast's old-fangled rules about fact checking. It appears in HIV denial (that is, early 1990s Sunday Times-style refusal to accept the scientific consensus about the cause of AIDS).

One reason the AskHistorians moderators are so unforgiving, Breit writes, is because it shares a host - Reddit - with myriad other subcommunities that are "notorious for their toxicity". I'd argue this is a feature as well as a bug: AskHistorians' regime would be vastly harder to maintain if there weren't other places where people can blow off steam and vent their favorite anti-matter. As much as I loathe a business that promotes dangerous and unhealthy practices in the name of "wellness", I'm still a free speech advocate - actual free speech, not persecuted-conservative-mythology free speech.

I agree with Breit that Zuckerberg's planned approach for Facebook won't work. But Breit's approach isn't applicable either because of scale: AskHistorians, with a clearly defined mission and real expert commenters, has 37 moderators. I can't begin to guess how many that would translate to for Facebook, where groups are defined but the communities that form around each individual poster are not. That said, if you agree with Breit about the purpose of JAQ, his approach is close to the one I've always favored: distinguishing between content and behavior.

Mostly , we need principles. Without them, we have a patchwork of reactions but no standards to debate. We need not to confuse Google and Facebook with the internet. And we need to think about the readers as well as posters. Finally, we need to understand the tradeoffs. History teaches us a lot about the price of abrogating free speech. The events of the last two years have taught us that our democracies can be undermined by hostile actors turning social media to their own purposes.

My suspicion is that it's the economic incentives underlying these businesses that have to be realigned, and that the solution to today's problems is less about limiting speech than about changing business models to favor meaningful connection rather than "engagement" (aka, outrage). That probably won't be enough by itself, but it's the part of the puzzle that is currently not getting enough attention..

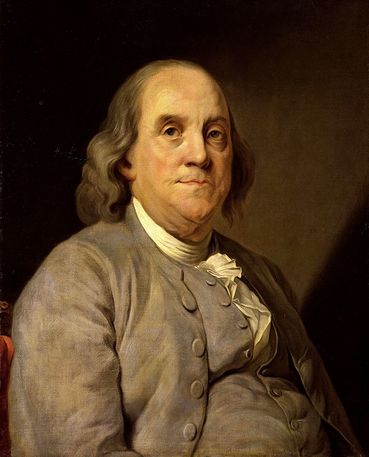

Illustrations: Benjamin Franklin, who said, "Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation must begin by subduing the freeness of speech."

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.