Legal friction

We normally think of the Internet Archive, founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle, as doing good things. With a mission of "universal access to all knowledge", it archives the web (including many of my otherwise lost articles), archives TV news footage and live concerts, and provides access to all sorts of information that would otherwise be lost.

We normally think of the Internet Archive, founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle, as doing good things. With a mission of "universal access to all knowledge", it archives the web (including many of my otherwise lost articles), archives TV news footage and live concerts, and provides access to all sorts of information that would otherwise be lost.

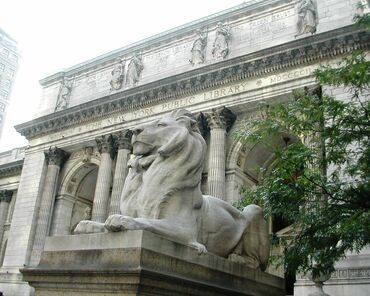

Equally, authors usually love libraries. Most grew up burrowed into the stacks, and for many libraries are an important channel to a wider public. A key element of the Archive's position in what follows rests on the 2007 California decision officially recognizing it as a library.

Early this year, myriad authors and publishers organizations - including the UK's Society of Authors and the US's Authors Guild - issued a joint statement attacking the Archive's Open Library project. In this "controlled digital lending" program, borrowers - anyone, via an Archive account - get two weeks to read ebooks, either online in the Archive's book reader or offline in a copy-protected format in Adobe Digital Editions.

What offends rights holders is that unlike the Gutenberg Project, which offers downloadable copies of works in the public domain, Open Library includes still-copyrighted modern works (including net.wars-the-book). The Archive believes this is legal "fair use".

You may, like me, wonder if the Archive is right. The few precedents are mixed. In 2000, "My MP3.com" let users stream CDs after proving ownership of a physical copy by inserting it in their CD drive. In the resulting lawsuit the court ruled MP3.com's database of digitized CDs an infringement, partly because it was a commercial, ad-supported service. Years later, Amazon does practically the same thing..

In 2004, Google Books began scanning libraries' book and magazine collections into a giant database that allows searchers to view scraps of interior text. In 2015, publishers lost their lawsuit. Google is a commercial company - but Google Books carries no ads (though it presumably does collect user data), and directs users to source copies from libraries or booksellers.

A third precedent, cited by the Authors Guild, is Capitol Records v. ReDigi. In that case, rulings have so far held that ReDigi's resale process, which transfers music purchased on iTunes from old to new owners means making new and therefore infringing copies. Since the same is true of everything from cochlear implants to reading a web page, this reasoning seems wrong.

Cambridge University Press v. Patton, filed in 2008 and still ongoing, has three publishers suing Georgia State University over its e-reserves system, which loans out course readings on CDL-type terms. In 2012, the district court ruled that most of this is fair use; appeal courts have so far mostly upheld that view.

The Georgia case is cited David R. Hansen and Kyle K. Courtney in their white paper defending CDL. As "format-shifting", they argue CDL is fair use because it replicates existing library lending. In their view, authors don't lose income because the libraries already bought copies, and it's all covered by fair use, no permission needed. One section of their paper focuses on helping libraries assess and minimize their legal risk. They concede their analysis is US-only.

From a geek standpoint, deliberately introducing friction into ebook lending in order to replicate the time it takes the book to find its way back into the stacks (for example) is silly, like requiring a guy with a flag on a horse to escort every motor car. And it doesn't really resolve the authors' main complaints: lack of permission and no payment. Of equal concern ought to be user complaints about zillions of OCR errors. The Authors Guild's complaint that saved ebooks "can be made readable by stripping DRM protection" is, true, but it's just as true of publishers' own DRM - so, wash.

To this non-lawyer, the white paper appears to make a reasonable case - for the US, where libraries enjoy wider fair use protection and there is no public lending right, which elsewhere pays royalties on borrowing that collection societies distribute proportionately to authors.

Outside the US, the Archive is probably screwed if anyone gets around to bringing a case. In the UK, for example, the "fair dealing" exceptions allowed in the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act (1988) are narrowly limited to "private study", and unless CDL is limited to students and researchers, its claim to legality appears much weaker.

The Authors Guild also argues that scanning in physical copies allows libraries to evade paying for library ebook licenses. The Guild's preference, extended collective licensing, has collection societies negotiating on behalf of authors. So that's at least two possible solutions to compensation: ECL, PLR.

Differentiating the Archive from commercial companies seems to me fair, even though the ask-forgiveness-not-permission attitude so pervasive in Silicon Valley is annoying. No author wants to be an indistinguishable bunch of bits an an undifferentiated giant pool of knowledge, but we all consume far more knowledge than we create. How little authors earn in general is sad, but not a legal argument: no one lied to us or forced us into the profession at gunpoint. Ebook lending is a tiny part of the challenges facing anyone in the profession now, and my best guess is that whatever the courts decide now eventually this dispute will just seem quaint.

Illustrations: New York Public Library (via pfhlai at Wikimedia).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.