A short history of the future

The years between 1995 and 1999 were a time when predicting the future was not a spectator sport. The lucky prognosticators gained luster from having their best predictions quoted and recirculated. The unlucky ones were often still lucky enough to have their worst ideas forgotten. I wince, personally, to recall (I don't dare actually reread) how profoundly I underestimated the impact of electronic commerce, although I can more happily point to predicting that new intermediaries would be the rule, not the disintermediation that everyone else seemed obsessed with.. Two things sparked this outburst: the uncertainty of fast-arriving technological change, and the onrushing new millennium.

The years between 1995 and 1999 were a time when predicting the future was not a spectator sport. The lucky prognosticators gained luster from having their best predictions quoted and recirculated. The unlucky ones were often still lucky enough to have their worst ideas forgotten. I wince, personally, to recall (I don't dare actually reread) how profoundly I underestimated the impact of electronic commerce, although I can more happily point to predicting that new intermediaries would be the rule, not the disintermediation that everyone else seemed obsessed with.. Two things sparked this outburst: the uncertainty of fast-arriving technological change, and the onrushing new millennium.

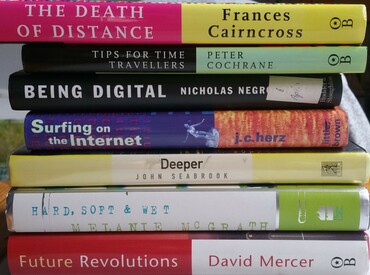

Those early books fell into several categories. First was travelogues: the Internet for people who never expected to go there (the joke would be on them except that the Old Net these books explored mostly doesn't exist any more, nor the Middle Net after it). These included John Seabrook's Deeper, Melanie McGrath's Hard, Soft, and Wet, and JC Herz's Surfing on the Internet. Second was futurology and techno-utopianism: Nicholas Negroponte's Being Digital, and Tips for Time Travellers, by Peter Cochrane, then head of BT Research. There were also well-filled categories of now-forgotten how-to books and, as now, computer crime. What interested me, then as now, was the conflict between old and new: hence net.wars-the-book and its sequel, From Anarchy to Power. The conflicts those books cover - cryptography, copyright, privacy, censorship, crime, pornography, bandwidth, money, and consumer protection - are ones were are still wrangling over.

A few were simply contrarian: in 1998, David Brin scandalized privacy advocates with The Transparent Society, in which he proposed that we should embrace surveillance, but ensure that it's fully universal. Privacy, I remember him saying at that year's Computers, Freedom, and Privacy, favors the rich and powerful. Today, instead, privacy is as unequally distributed as money.

Among all these, one book had its own class: Frances Cairncross's The Death of Distance. For one thing, at that time writing about the Internet was almost entirely an American pastime (exceptions above: Cochrane and McGrath). For another, unlike almost everyone else, she didn't seem to have written her book by hanging around either social spaces on the Internet itself or in a technology lab or boardroom where next steps were being plotted out and invented. Most of us wrote about the Internet because we were personally fascinated by it. Cairncross, a journalist with The Economist studied it like a bug pinned to cardboard under a microscope. What was this bug? And what could it *do*? What did it mean for businesses and industries?

To answer those questions she did - oh, think of it - *research*. Not the kind that involves reading Usenet for hours on end, either: real stuff on industries and business models.

"I was interested in the economic impact it was going to have," she said the other day. Cairncross's current interest is the future of local news; early this year she donated her name to the government-commissioned review of that industry. Ironically, both because of her present interest and because of her book's title, she says the key thing she missed in considering the impact of collapsing communications costs and therefore distance was the important of closeness and the complexity of local supply chains. It may seem obvious in hindsight, now that three of the globe's top six largest companies by market capitalization are technology giants located within 15 miles of each other in Silicon Valley (the other two are 800 miles north, in Seattle).

The person who got that right was Michael Porter, who argued in 1998 that clusters mattered. Clusters allow ecosystems to develop to provide services and supplies, as well as attract skills and talent.

Still, Cairncross was right about quite a few things. She correctly predicted that the inequality of wages would grow within countries (and, she thought, narrow between countries); she was certainly right about the ongoing difficulty of enforcing laws restricting the flow of information - copyright, libel, bans on child abuse imagery; the increased value of brands; and the concentration that would occur in industries where networks matter. On the other hand, she suggested people would accept increased levels of surveillance in return for reduced crime; when she was writing, the studies showing cameras were not effective were not well-known. Certainly, we've got the increased surveillance either way.

More important, she wrote about the Internet in a way that those of us entranced with it did not, offering a dispassionate view even where she saw - and missed - the same trends everyone else did. Almost everyone missed how much mobile would take over. It wasn't exactly an age thing; more that if you came onto the Internet with big monitors and real keyboards it was hard to give them up -and if you remember having to wait to do things until you were in the right location your expectations are lower.

I think Cairncross's secret, insofar as she had one, was that she didn't see the Internet, as so many of us did, as a green field she could remake in her own desired image. There's a lesson there for would-be futurologists: don't fall in love with the thing whose future you're predicting, just like they tell journalists not to sleep with the rock stars.

Illustrations: Late 1990s books.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.