The inside view

So many lessons, so little time.

So many lessons, so little time.

We have learned a lot about Facebook in the last ten days, at least some of it new. Much of it is from a single source, the documents exfiltrated and published by Frances Haugen.

We knew - because Haugen is not the first to say so - that the company is driven by profits and a tendency to view its systemic problems as PR issues. We knew less about the math. One of the more novel points in Haugen's Senate testimony on Tuesday was her explanation of why Facebook will always be poorly moderated outside the US: safety does not scale. Safety costs the same for each new country Facebook adds - but each new country is also a progressively smaller market than the last. Consequence: the cost-benefit analysis fails. Currently, Haugen said, Facebook only covers 50 of the world's approximately 500 languages, and even in some of those cases the country does not have local experts to help understand the culture. What hope for the rest?

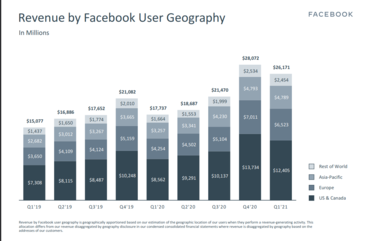

Additional data: at the New York Times, Kate Klonick checks Facebook's SEC filings to find that average revenue per North American user per *quarter* was $53.56 in the last quarter of 2020, compared to $16.87 for Europe, $4.05 for Asia, and $2.77 for the rest of the world. Therefore, Klonick said at In Lieu of Fun, most of its content moderation money is spent in the US, which has less than 10% of the service's users. All those revenue numbers dropped slightly in Q1 2021.

We knew that in some countries Facebook is the only Internet people can afford to access. We *thought* that it only represented a single point of failure in those countries. Now we know that when Facebook's routing goes down - its DNS and BGP routing were knocked out by a "maintenance error" - the damage can spread to other parts of the Internet. The whole point of the Internet was to provide communications in case of a bomb outage. This is bad.

As a corollary, the panic over losing connections to friends and customers even in countries where social pressure, not data plans, ties people to Facebook is a sign of monopoly. Haugen, like Kevin Roose in the New York Times, sees signs of desperation in the documents she leaked. This company knows its most profitable audiences are aging; Facebook is now for "old people". The tweens are over at Snapchat, TikTok, and even Telegram, which added 70 million signups in the six hours Facebook was out.

We already knew Facebook's business model was toxic, a problem it shares with numerous other data-driven companies not currently in the spotlight. A key difference: Zuckerberg's unassailable control of his company's voting shares. The eight SEC complaints Haugen has filed is the first potential dent in that.

Like Matt Stoller, I appreciate a lot of Haugen's ideas for remediation: pushing people to open links before sharing, and modifying Section 230 to make platforms responsible for their algorithmic amplification, an idea also suggested by fellow data scientist Roddy Lindsay and British technology journalist Charles Arthur in his new book, Social Warming. For Stoller, these are just tweaks to how Facebook works. Haugen says she wants to "save" Facebook, not harm it. Neither her changes nor Zuckerberg's call for government regulation touch its concentrated power. Stoller wants "radical decentralization". Arthur wants cap social network size.

One fundamental mistake may be to think of Facebook as *a* monopoly rather than several at once. As an economic monopoly, businesses all over the world depend on Facebook and subsidiaries to reach their customers, and advertisers have nowhere else to go. Despite last year's pledged advertising boycott over hate speech on Facebook, since Haugen's revelations began, advertisers have been notably silent. As a social monopoly, Facebook's outage was disastrous in regions where both humanitarians and vulnerable people rely on it for lifesaving connections; in richer countries, the inertia of established connections leaves Facebook in control of large swaths of our social and community networks. This week taught us that its size also threatens infrastructure. Each of these calls for a different approach.

Stoller has several suggestions for crashing Facebook's monopoly power, one of which is to ban surveillance advertising. But he rejects regulation and downplays the crucial element of interoperability; create a standard so that messaging can flow between platforms, and you've dismantled customer lock-in. The result would be much more like the decentralized Internet of the 1990s.

Greater transparency would help; just two months ago Facebook shut down independent research into content interactions and its political advertising - and tried to blame the Federal Trade Commission.

This is *not* a lesson. Whatever we have learned Mark Zuckerberg has not. At CNN, Donie O'Sullivan fact-checks Zuckerberg's response.

A day after Haugen's testimony, Zuckerberg wrote (on Facebook, requiring a login): "I think most of us just don't recognize the false picture of the company that is being painted." Cue Robert Burns: "O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us | To see oursels as ithers see us!" But really, how blinkered do you have to be to not recognize that if your motto is Move fast and break things people are going to blame you for the broken stuff everywhere?

Illustrations: Slide showing revenue by Facebook user geography from its Q1 2021 SEC filing.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.